No matter how you take notes, doing so is critical for understanding, retention, and review. Whether you’re taking lecture notes or jotting down things from a meeting, writing things down makes your life significantly easier.

Here we’ll discuss type written versus handwritten, seven popular ways of note-taking, and strategies for better note-taking.

Ready? Let’s dive in.

Digital Note-Taking vs. Handwritten?

The age-old debate with note-taking is typed versus handwritten notes. Let’s break down the pros and cons of each method.

Typed

Pros:

- Most of us type much faster, so we can take more information down, which is helpful if you’re recording lecture content

- Better for organizing notes, flexible formatting, easy to add in spaces for more info

- Easier to read

- Easy to add, change, or delete information

- Typing isn’t that tiring, so you can keep up with longer meetings

Cons:

- Since you can type more, you won’t be forced to summarize or draw your own conclusions for the sake of clarity. Summarizing promotes retention and maximum learning.

- More inclined to type verbatim, even recording useless words

- Computers are incredibly distracting, with notifications and internet access

Handwritten

Pros:

- Handwritten notes increase short-term and long-term retention

- Forces active listening, which promotes better understanding

- Easier time applying material

- Writing forces you to synthesize, which promotes in-depth knowledge

- Less distracting

- Customization with drawings and sketches

- Forces you to focus on only relevant content

Cons:

- Much slower, so it may not be as suited for longer or denser meetings

- Hard to amend or reformat written notes

- Possibly illegible

Which is better for taking effective notes?

Ultimately, whether handwritten notes or typed notes are better depends on personal preference. If you’re in a meeting where getting all the information is more critical than retention, type notes. If your situation is less dense, but you want to recall details better and apply knowledge, write by hand.

You can also write notes and type them later, allowing your brain to go back over the material and transform them into a legible, organized form.

Popular Note-Taking Methods

The Outline Note-Taking Method

The outline format is one of the oldest and most popular note-taking formats out there. While it’s nothing particularly fancy, it’s more efficient and logical.

Here’s how this method works:

- Main topics on the left

- Supporting information is added with another indent

- Further details are noted with one more indentation

- Subtopics are added below main topics with an indent

- Supporting information is added with another indent

This logical structure clarifies how the information relates to itself; the indentation indicates the importance and level of information. Indents are made using bullets, numbers, dashes, or other symbols to help break the content down into essential points.

According to Kenneth A. Kiewera, who published over 20 research papers on this note-taking method between 1984 – 1995, the outline method bears two benefits:

- It makes superordinate and subordinate relations obvious, making topics easier to understand

- Outline organization of topics and subtopics helps with knowledge retention and makes retrieving information easier

To properly use this strategy, you’ll want to do the following:

- Gather note-taking materials. This can include a notebook, writing utensil, and work area.

- Outline the main topics. There shouldn’t be many main topics; even one is sufficient. This is how you’ll organize the entire set of notes, and you’ll want to keep it succinct. Main topics should be broad enough to add subtopics and further information but specific enough that you aren’t spread too thin and adding tons of them.

- Outline subtopics. Remember, these are added with one indentation under the main topics. You’re likely to end up with a lot of these.

- Supporting information. Now it’s time to get specific. Main and subtopics are just that: topics. You’ll need to add in any relevant information, from facts to features to dates, or even your own thoughts.

- Further details. Lastly, insert any unmentioned information that you feel is relevant. You can write short sentences, key concepts, or draw diagrams.

The Sentence Method

The idea behind this note-taking practice is to separate new thoughts by new lines and sentences. Whenever a new concept is introduced, you write it on another line.

This is a minimal approach and is often used for casual note-taking such as jotting things down from a phone call.

Some pros of this method include:

- Easy to use during fast-paced meetings or lecture situations

- Easy to apply to any context

Some cons include:

- Poor organization

- Lack of clear spatial relationships between points

- Reviewing notes is time-consuming

- Shows no connections between thoughts

- No distinction between main and subtopics

There are some positives, but there are primarily drawbacks to this method. It should be readily avoided unless you have no other choice.

Here’s exactly how you would apply the sentence method:

- Write each sentence on its own line. You’ll have to think quickly in order to record each new concept or idea onto its own line. You’ll want to write in shorthand to decrease the amount of information you have to take down.

- Number each line so you can better review the info later.

- Review what you wrote. Since notes are written relatively haphazardly, it’s challenging to properly review them and synthesize information after the meeting. For this reason, we recommend avoiding this method unless you have no other choice and choosing a more well-organized system.

The Cornell Method

Perhaps one of the most touted methods, Cornell notes, help foster the natural learning cycle by forcing active engagement and active participation. Developed by Walter Pauk, director of Cornell University’s Reading and Study Skills Center, this note-taking system took off since its inception in 1962.

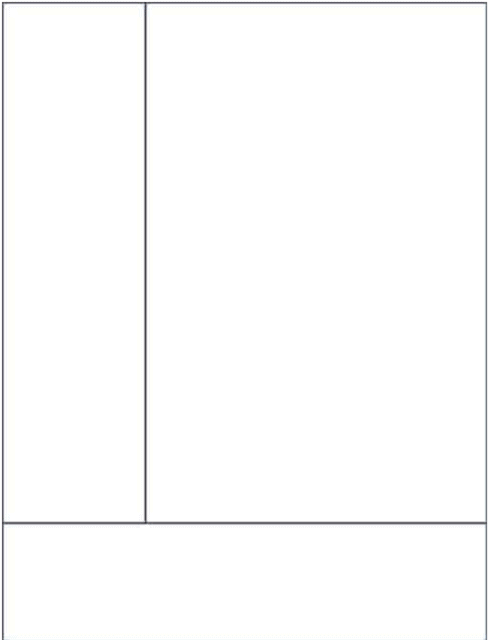

Cornell notes involve dividing a paper into three sections: questions in the left-hand column, notes in the right-hand column, and summary area. This forces you to understand information better and is used for all sorts of note-taking.

What your sheet should look like for Cornell notes

Surprisingly, Cornell itself uncovered through its free Note-Taking Strategies module that most students want to use their notes to study, but most never actually use them. By implementing the Cornell method, your notes will be in strong enough shape to study effectively.

You can purchase pre-designed Cornell pads, or you can divide up a piece of paper into the Cornell format on your own. The pads may save time and look neater, but the cost adds up; however, it’s your choice.

Here’s how to properly use the Cornell method:

- Referencing the image above, you’ll want to record your primary notes in the large main column. This is where you take down the essential points and key concepts. Use short sentences and shorthand to ensure you’re getting down all relevant information. You could also add drawings, concept maps, or graphics to your notes column. To help with studying later, you can add bulleted or numbered lists to this column for skimmability.

- Retroactively, fill your question/cue column on the left side. This is done after the primary note-taking because it forces you to synthesize and ask questions about all the info you took down. You can also fill this in as you go along but make additions later.

- Make summaries in the bottom section to mention all important points discussed on the page. This should be a few sentences in length.

- When studying, cover the notes column and use the questions or cues from the left-hand column to quiz yourself. Look back at the notes column – did you get it right?

The Mapping Method

The mapping method is challenging, but when done correctly, it pays off. It originates from Tony Buzan, an English author, and consultant. In his book “The Mind Map Book,” he drew attention to this technique, and when the book took off, the mapping method was popularized.

It’s worth noting that based on modern research, some of the theory behind Buzan’s book is incorrect. He believed that the human brain is divided into the left and right sides and that the two don’t communicate; in 2013, a two-year study concluded that our hemispheres do talk to each other, and we constantly receive input from both.

Nonetheless, the mapping method remains impactful. It’s best suited for material that’s detailed and targeted. When all categories or subcategories are linked to the main topic, whether directly or indirectly, the mapping method shines, and it gives you a graphic representation of all the information.

That said, the efficacy of this method is up for debate according to the literature, but that doesn’t render it useless.

Pros of the mapping method:

- Easy to edit with additional information

- Relationships between concepts are easy to see

- Pictures and graphics help visual learners

- Efficient to review notes from lectures

Cons of the mapping method:

- Often used alongside other methods

- Strong concentration necessary

- It can quickly become overwhelming for some subjects

- Hard to distinguish thoughts and facts

- It doesn’t always work well, depending on the lecture format

Here’s how to properly take mapping notes:

- Write down your main topic. This needs to be the central focus point of the entire map, so select it carefully. If you don’t get it right, you’ll need to remap your notes; that’s incredibly time-consuming and frustrating! Go for something broad enough that you can map onto it but not so broad that it encompasses too much.

- Add and connect subtopics. If you’re talking about car features, subtopics might be fuel efficiency, horsepower, towing capacity, seating capacity, and so on. Jot these down below and around the main topics, draw circles around them, and connect them to the appropriate main topic.

- Add supporting ideas. Repeat the above step for supporting information. Some concepts don’t require the addition of supporting ideas, so skip to the next step.

- Include further information. You don’t need to circle each idea anymore, as this is the final mapping step. Supporting ideas clearly branch out into this additional information, making it clear to understand. You can also start color-coding main ideas, subtopics, supporting ideas, and further details, so they’re easier to distinguish.

- Review the map. Begin covering lines from different circles and testing if you can recall them. You may also want to review source material during this process, as mapped notes are relatively barren.

The Boxing Method

The boxing method is a relatively new style of note-taking developed for digital tools. It takes advantage of digital offerings such as shape, lasso, or drawing tools. This method uses boxes to visually separate topics, and thoughts or ideas are written vertically to form clusters of related information.

The boxing method is best suited for subjects with fewer subcategories and smaller clusters of information. Although this was originally designed for digital note-takers, it works well for handwritten notes, too. The only difference is that you can’t shift information around on paper with a lasso tool as you can digitally, so pay special attention to positioning.

Pros of the boxing method:

- Easy to review and revise

- Perfect for digital note-takers

- Aids with visual learning

- Reduce information without rewriting

Cons of the boxing method:

- Time-intensive, so it won’t work for fast-paced classes or meetings

- Easily distracted by making the aesthetics perfect

- Requires intense focus

Here’s how to properly apply the boxing method:

- Create columns and headings. Split your piece of paper into columns to represent topics. Add headings atop the columns. Horizontal pages are suited to two columns, where vertical pages can accommodate three or four.

- Add notes to columns. Summarize new pieces of information and add them to the appropriate columns. Place information carefully, as that’s how the boxing method works. Use abbreviations and shorthand wherever you can to take more notes.

- Move, edit, and resize. This only applies to digital devices, but it can help you reorganize your notes. When reviewing, you may notice that some notes need to be split up or rearranged, and digital tech allows you to do that.

- Draw boxes. This is where the boxing method gets its name. Since you’ve separated information by topic previously, you’ll need to add boxes around them. You can separate large boxes with lots of information into smaller ones.

- Review. Cover information by topic and review the notes within 24 hours for maximum retention.

The Charting Method

As the name suggests, the charting method uses charts to organize and condense notes. You split your document into rows and columns and add in summaries of information. Each column has its own category, and each row has its own topic.

Since this method uses charts, you can take notes directly in Excel or Sheets; however, other software like Word or Docs allows for the insertion of charts.

The charting method is best suited for topics with large quantities of facts or statistics. It’s also appropriate for subtopics that are comparable and information that can be compartmentalized. It won’t be suited for taking notes live, topics with vast detail, or noting spatial relationships.

To properly take notes with the charting method, follow these steps:

- Categories and topics. You need to analyze materials before taking notes, so you’ll need to establish topics and categories in your prep. Ascertain the main topic, subtopics, and categories of information. If you’re struggling to find categories, then the charting method likely isn’t the right one for that material.

- Make a new chart. Whether you use Excel or Sheets or instead insert tables into other documents, create your chart and add an extra notes column to it. You can also add background colors to different columns to help distinguish information.

- Add categories, topics, and subtopics. Combine steps one and two, and prepare your chart for note-taking.

- Take notes. Within the appropriate topics, categories, and subtopics, begin inserting your notes. Since your chart was previously prepared, you can focus on writing and retaining relevant material.

- Review. Given the layout of your charts, you can memorize material by topic or category.

SQ3R

This note-taking method is a complicated one, so much so that the founder of Cornell notes, Walter Pauk called it too complex for students.

SQ3R stands for survey, question, read, recite, review, or the exact process of using these notes. It was originally developed by Francis P. Robinson in 1941.

Although the jury’s still out on the conclusion of this method’s effectiveness, various studies found benefits of note-taking with this method:

- SQ3R requires you to use processing systems more effectively

- Develops better critical thinking, organizational, and association skills

- It helps you retain more information.

Some disadvantages include:

- Steep learning curve

- Time-intensive

- Difficult to learn and apply

- It doesn’t help with organization or integration

- Only suited to written material

Here are the steps to the SQ3R method:

- Survey. Preparing your brain for what’s to come helps it store information more efficiently, as it knows what to expect. First, review your material and skim headings and subheadings. Review other details such as images, tables, or diagrams. Skim the first sentence of each paragraph and review summaries. Keep this quick, under 3-5 minutes.

- Question. Once you’ve reviewed the material, formulate questions around if so, you know what information to pay attention to. Although generating questions is more complicated, it can pay off.

- Read. Start reading the information and answer self-generated and provided questions. This method is now forcing you to read actively; this takes far more cognitive effort.

- Recite. This step is very time-consuming. Put all your transcribed notes into your own words and cover major points. This helps bring information from short-term into long-term storage.

- Review. Check all headings identified in step one and summarize information into your own words. This immediate review of notes after class or a meeting helps prevent you from quickly forgetting the material.

Strategies For Better Note Taking

Be actively engaged

Although it’s tempting to be distracted, being engaged and asking questions helps you take more robust notes.

Review before classes or meetings

Before lectures or meetings, review agendas, textbook chapters, or any other material, this gives you an idea of what you’re learning and prepares your brain.

Review notes after class or a meeting

Humans tend to forget information that isn’t thought about immediately. To encode information from short-term into long-term memory, review everything thoroughly after the event.

Use shortcode

To help you jot more information down, use abbreviations, bulleted lists, symbols, and drawings to speed up the process.

Be legible

If you aren’t typing, focus on writing clearly. Notes are useless if you can’t read them afterward.

Be organized

Use one of the note-taking methods above and keep everything organized. This ensures you can quickly review the notes and understand the material.

Conclusion

There are various methods of note-taking you can use, and which one you choose depends on personal preference and the material. Whether you prefer physical methods or digital, writing things down will greatly help with retention and review.

Which will you try first?