This is a guest post by Dean Palibroda of OrganizedandProductive.com. Dean’s spent the last 10+ years traveling North America learning from experts and gurus in the areas of personal and professional development.

Be sure to check out the interview Dean did with Zach for his podcast.

If you’re anything like me, you don’t remember much from your college days. We learn information for tests, and then it’s gone.

Eventually we want (or need) to pick up unfamiliar skills outside of college, from blogging to web design to car repair to gardening.

The problem is rarely motivation, difficulty, or even time. The problem is technique.

College is about memorization, passing tests, and getting grades. But out in the real world, we care about action and results.

A study conducted by the Wall Street Journal found that 4 out of 10 graduating seniors lack the critical-thinking ability to make it in a white collar job.

White collar job doesn’t just mean office drones, either. We’re talking about engineers, chemists, and politicians, too. That means for at least 40% of students, the “college way” just isn’t ideal for processing and truly understanding information.

In this great article on memorization and learning, the author discusses how rote memorization can actually prevent you from making important observations.

Basically, he says that blindly recalling information (like for a final exam) isn’t the same as understanding that information. Knowing who signed the Declaration of Independence on which date in which city versus what the Declaration actually means, or memorizing an equation versus understanding why that equation works.

Self-education isn’t impossible or even difficult, it’s just different from what you’re used to.

Step 1: Read/listen to/watch your target material and take notes

The first step is the most obvious and most frequently overlooked.

We don’t like to take notes. Let’s face it, after years of school we can’t help but associate note-taking with boredom. But jotting down notes is absolutely vital.

When it comes to long-term memory, nothing beats writing.

Research conducted at Princeton University’s psychology department examined the difference between digital and manual notetakers to see which were more successful.

Turns out, the speed with which we can take notes by typing is also a double-edged sword. Because we can type faster than we write, we often transcribe our target material (lecture, book, online course) word-for-word.

Writing with a pen and paper, on the other hand, forces us to get down the same ideas in our own words.

There are two categories of notes you should be taking.

The first covers mindsets needed for success in your area of study, while the second category includes steps or methods involving the technical aspects of taking action.

For example, if you were teaching yourself the ins and outs of WordPress blogging, you might write down a figure showing how and why the vast majority of new blogs fail in order to avoid the same mental pitfalls.

You would also outline the path to success taken by some of the most popular blogs, noting what worked, what didn’t, and how their lessons can help you skip the growing pains of a new blog.

A budding pianist would want to get inside the heads of the greatest musicians, recording exactly what they felt each time they sat down to play. What attitudes help them get in the zone?

You’d also be interested in a step-by-step process for building muscle memory, keeping track of all the piano’s keys, and how to maintain proper posture and breathing.

If you’re using a physical book, take notes in the margins. This “marginalia” can be used to ask questions about the text, highlight unknown words, or simply summarize dense information.

With an ebook, you can almost do the same thing. Most ereader apps support highlighting and note-taking, but your initial source of notes should still be handwritten.

Step 2: Type up your first batch of notes on your computer

But that’s not to say computers have no place in our learning process.

Typing up your notes fulfills several purposes—it forces you to review the material, add in any information you missed, and reorganize the material. It’s also more practical for storing a large amount of information.

Right now we need to consolidate our notes to make them more legible. Sometimes you’ll need to rearrange paragraphs, bullet points, or even whole chapters’ worth of material.

Say you’re studying Spanish, and your course’s final online module covers useful slang. Maybe it makes more sense to break that information down and mix that vocab with preceding modules—food with food, dating with dating, etc.

Depending on your subject, it might make sense to order your notes completely differently from their source. Don’t worry about conventions or proper formatting so much as logic and user-friendliness.

At this point, feel free to throw away your handwritten notes.

Step 3: Reread/watch/listen to your material

Like taking notes, you probably want to skip this step, too. But it’s actually a lot easier to read a book the second time.

At this point you already have copious notes. The point of rereading or revisiting your target isn’t to take the same notes, but to pick up what you missed.

A lot of what you review—maybe even most of it—will be familiar. But you’re looking for those few pieces of gold that slipped through the cracks on your first visit. Often, those last nuggets are the most valuable.

In this article on the value of rereading, the author examines the reasons why students who simply reread source material often find they can’t recall much of it.

You’ve got to become an active rereader, and that’s where your marginalia and notes come in. Each note will jog your memory and make you see the material in a new light, helping you make connections that weren’t possible on your first trip.

Now that you’ve squeezed the last bit of knowledge from your source material, add it to your growing text document.

Look at all of your gathered thoughts with a fresh set of eyes. Give it a day or two if you have to.

Now it’s time to cull the herd. After going over your course or book twice and removing the vital bits, some of your notes aren’t going to seem very important. What you thought was an awesome quote or a great statistic maybe isn’t that fantastic.

If they don’t add value or help you understand the subject better, get rid of them. Now you’re left with the concentrated essence of the material.

Step 4: Turn your notes into a notecard library

While your computer is great for aggregating the vital parts of your notes, it’s not the best choice for long-term organization or review.

Notecards are ideal for two reasons:

- Their size forces you to focus on vital pieces of information;

- And a stack of notecards is much easier to flip through than a crowded text document.

Robert Greene, author of multiple best-selling books like The 48 Laws of Power, is a prolific researcher—and consequently an avid notetaker.

His books represent the combined knowledge of hundreds and hundreds of works by previous authors, all connected and concentrated using an underlying theme.

You probably see parallels between gathering research for a book and self-study using an online course or book; understanding what’s important is just as critical as knowing what to toss out.

In this article examining Robert’s research strategy, we can see that the end product of his voracious appetite for books is a massive library of notecards, all categorized by theme.

Robert’s protégé, Ryan Holiday, makes great use of the same system, both for his personal reading list and for research.

It’s not as complicated as you think. Unless you plan on writing an award-winning book, you’re probably not going to need thousands of cards.

Don’t be afraid to cut down your text document even more. These cards shouldn’t be packed with words. Keep each card to a few sentences, maybe a paragraph at most.

The goal here is not to transfer your entire computer file back into manuscript. Remember, Robert Greene winds up with a small stack of just 20 to 30 cards for a good book.

Think of it this way: you started with a book, online course, whatever. You took personalized notes. You organized those notes and cut the junk. Now you’re organizing and eliminating yet again. What’s left is the absolute best, most insightful, and useful knowledge from that original source.

For each piece of knowledge, assign it a theme. For your self-guided freelancing course, those themes could be:

- Finding clients;

- Professionalism;

- Bookkeeping;

- Organization and productivity, etc.

Robert Greene also color-codes his cards, but it’s really up to you.

Step 5: Review, review, review

Not everyone wants to read dozens of books per month like Ryan Holiday or Robert Greene. But the beauty of this notecard system is its adaptability.

If you’ve ever tried to review for an exam by rereading a whole textbook, you know it’s inefficient. But how about rereading an entire book in just a few dozen 3 x 5 index cards?

Without the useless filler from your source material, you can review an entire book or course—one that could take a week to completely review—in just a few hours.

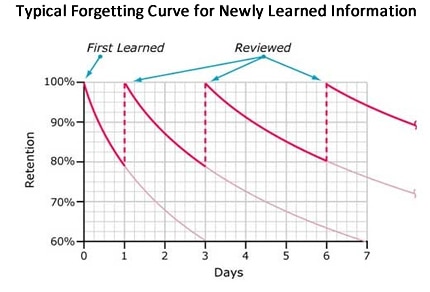

Below we can see the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve. When we learn new info, gradually (without review) bits and pieces of that knowledge are lost.

Using periodic review, we can “reset” that curve, eventually slowing memory loss to a trickle.

When you look at these cards, don’t just memorize their content. Your goal should not be to quickly flip through your stack like arithmetic flashcards.

Use the cards to form links to experiences you’ve had from taking action.

Step 6: Make learning a lifelong habit

But, say you can read a short book on coding with Javascript in 30 hours. Tack on another 10 hours to take notes. Another 2 hours to consolidate, 15 more to reread the book, plus another 3 hours to transfer those notes to index cards. We’re looking at doubling your time investment in each book, give or take.

It’s not about volume. Learning is about taking action and getting results.

According to Dr. Wyatt Woodsmall, “Learning only occurs when there is behavioral change.”

Replacing a fuel filter, playing the piano, or optimizing your site’s SEO are behavioral changes indicative of learning. Your notecard library must help you achieve an actionable goal or get measurable results.

It sounds like a lot of effort, but there’s a simple solution to find more time for your studies.

Julien Blanc put out a great video on mastering skills and how to make time for learning.

He gives an example of cutting out just one hour of wasted time every day and replacing it with reading. At the end of the year, you’ve spent an extra 365 hours educating yourself that would have otherwise gone to waste and added no value to your life.

Even if you focus on quality over quantity, odds are one course or book isn’t going to be enough to teach you all about an intricate topic. Stick with the system, keep adding to your library, use periodic review, and synthesize knowledge from a wide variety of sources.

This constant reconciliation of the old and the new is the basis of constructivist learning, which treats the learner as an active participant, not a passive bystander like students in a lecture hall.

What seemed interesting last month could become inspiration or the solution to a tough problem down the line—a problem you couldn’t foresee when you first started.

Essentially, this is Google for your life. No distractions, no irrelevant search results, no wasted time.

Be sure to visit OrganizedandProductive.com for more time management and productivity tips.

If you’re ever lacking in the motivation department, bookmark this video Dean put together:

I love the notecard implementation! If I may add they are also ideal in terms of rearranging ideas across different sources since they are not tied down as in a bound notebook.

Out of curiosity, after you complete your notecards, do you digitize them or just leave them as is?